Sailing to the South Pacific in the 1700s and 1800s must have seemed like riding a bicycle to the moon, but the Maritime Museum of San Diego shows how three adventurers did just that. Three connected narratives thread together the adventures of explorer Captain James Cook, author and merchant seaman Herman Melville, and post-impressionist artist Paul Gauguin and how they (almost) discovered paradise. A first-of-its-kind exhibit for the Maritime Museum, Cook, Melville and Gauguin: Three Voyages to Paradise, on view through January 1, 2012, features over 150 pieces from Cook’s, Melville’s and Gauguin’s travels, selected from the Kelton Foundation’s extensive collections of original paintings, engravings, whaling artifacts, writings, woodblock prints, rare wood carvings and sculptures.

The story begins in the museum-ship’s hold: “Against the history of the world’s greatest ocean as a vast, empty, deadly, and dark place, three voyagers won enduring fame through reinventing a Pacific in the collective imagination of humanity as the location of earthly paradise.” Evidently, mass audiences of the time “possessed unquenchable appetites for adventurous travel, romantic settings, and to imagine society as a more simple, noble, and perfect version of itself when transposed into a natural setting of endless beauty and bounty: a return to Eden.”

The three stories, though distinct, do blend into each other, as mythmaking should (though I overhear someone attributing Cook’s commissioned artist’s work to Captain Cook himself and referring to Melville as a painter instead of a writer). It’s tempting to spend time with the navigational instruments and charts, and learn more about Cook’s tragic final voyage and Melville’s return to a civil servant career after the failure of Moby Dick, but Gauguin’s heart of darkness is too much of a draw. The impact of arriving at this display of his three-dimensional masterpieces – the largest ever shown – overrides the previous work.

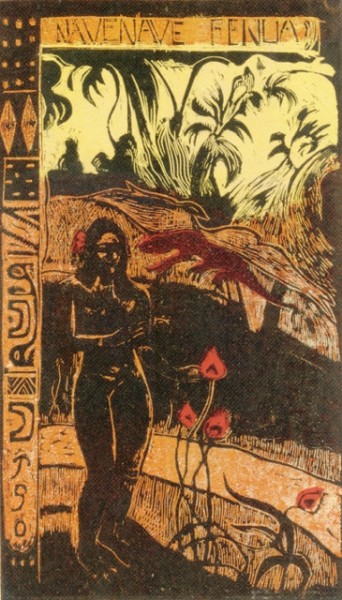

The collection offers insight into Gauguin himself. In a self-published newsletter, the artist advocates for change on an island becoming ever more corrupt by its settlers. Over time, his paint palette progresses to darker hues. His woodblock prints reveal alternative prints on their backings, and traditional busts progressively morph into sculptures of humans combined with gods and animal spirits. At this point, I’m reminded of the Wernor Herzog documentary Cave of Forgotten Dreams, in which it’s discussed that cave dwellers did not distinguish themselves from their surroundings in their art; instead, they fused their own bodies with the heads of animals. This seems to identify the late Gauguin in Tahiti – in a sense returned to a beautiful bestiary self, definitely not Eden.